A salute to some notables who do not deserve to be forgotten as we head into the new year.

DICK BUTTON (1929-2025)

When Richard Totten Button was 12, he asked his father if he could trade a pair of hockey skates for figure skates. He was short and pudgy at the time and showed little promise. But after a summer of training in Lake Placid, New York, with Swiss-born coach Gustave Lussi, he quickly became adept at the sport. “I never remember a time I did not like skating,” he said in a 2010 video. “There was an excitement about the freedom of it, the ability to move — it was like flying. Something magical happened with it.”

While working on mastering the “compulsory” figures that gave the sport its name, he also developed his own dynamic, artistically compelling five-minute free-skate routine. He also outraged the conservative world of European figure skating by choosing to skate in a white waiter’s jacket and standard trousers instead of a black fitted jacket and tights. “Nobody knew who I was. Nobody knew what American skating was,” he told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune in 1988. “I didn’t want to look like everybody else.”

In 1948, he won the first of five straight world titles, and the gold at the Winter Olympics. He entered Harvard later that year to study law – though he did get his law degree and passed the bar exam, he never put it to practice. Instead, he kept on skating. At the 1952 Winter Olympics, he became the first person to land a triple jump in competition – along the way to another gold medal:

After that, he turned “pro”, signing a contract with the Ice Capades that made him one of the highest paid athletes in the country. In 1960, he covered figure skating for CBS when they broadcast that year’s Winter Olympics. He’d join ABC Sports two years later, launching his second career as a commentator.

He’d cover the sport in a way never before seen or heard, as if he were a critic covering the opera or ballet. He saw figure skating as a rare blend of athleticism and artistry. “It has music, it has choreography, it has personality,” he said. “You watch it not to see only who wins, but to see how they win.” And he wasn’t afraid to slam a skater, costume, or program if he felt it was deserved. “That was an angry tango,” he said of one less-than-sublime Olympic ice dancing routine. He described another performance as “slapped together without very much thought or intelligence.” When he was accused of describing a skater’s maneuver as “an ugly, ugly position,” he replied with aplomb: “That is wrong. I only said ‘ugly’ once. And it was an ugly position.”

Explaining the Compulsory Figures:

He’d cover the Winter Olympics with ABC from 1964 through 1988, coming back to the Games for the 2006 Olympics in Turin and the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver. Along the way, he organized the World Professional Figure Skating Championships, a tour for professional skaters, and created other sports entertainment programming, including “The Superstars” and “Battle of the Network Stars”. He’d be named to the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame, the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame, and the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame.

In the decades since Mr. Button dominated his sport, no American male skater came close to matching his record of two Olympic gold medals and seven national championships. “I’ve always found that all through the competition, the really exciting thing that happened was skating well, making your body do what you want,” he once told NPR. “That was the reward, much more than any medal.”

At the 2018 U.S. Figure Skating Championships:

PAUL EKMAN (1934-2025)

Before he even graduated from high school, Ekman enrolled at the University of Chicago where he studied psychology. He’d earn his BA at NYU in 1954, focusing on facial expressions and body movement. A grant from the National Institute of Mental Health allowed him to continue his work; the grant would be renewed for forty years.

He would soon note a strong correlation between emotions and specific expressions across all manner of societies, which ran counter to the prevailing theory that expressions for things like joy and anger were learned. With his colleague Wallace V. Friesen, he would categorize the many little movements that create a facial expression. The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) — a comprehensive tool for measuring facial movement – was the result. The FACS was first published in 1978 and revised in 2002. It allows trained individuals to categorize facial movements based on the specific muscles involved in an expression.

Ekman would develop this work into a way to help detect when a person is lying. His work is frequently referred to in the TV series Lie to Me where he served as scientific advisor and whose character Dr. Lightman is based on him. He also worked with Pixar’s film director and animator Pete Docter as a scientific consultant for the latter’s 2015 film Inside Out.

He did have some minor issues with that movie’s portrayal of Sadness. “Sadness is seen as a drag, a sluggish character that Joy literally has to drag around through Riley’s mind…In the film, Sadness is frumpy and off-putting. More often in real life, one person’s sadness pulls other people in to comfort and help,” he explained.

After the release of Inside Out 2, Ekman noted he hoped a third movie in the series would include the emotion of compassion. As for Inside Out 2, he wrote, “All in all, it was a joy to watch and feel along” with the film.

FREDERICK FORSYTH (1938-2025)

Born in Kent, England, Forsyth joined the RAF at the age of 18 before becoming a war correspondent for the BBC and Reuters. He revealed in 2015 he also worked for British intelligence agency MI6 for more than 20 years.

1970 found him “in debt, no flat, no car, no nothing and I just thought, ‘How do I get myself out of this hole?’ And I came up with probably the zaniest solution – write a novel,” he said. Drawing on his experience around the world, he penned a thriller set in 1963, about an Englishman hired to assassinate the French president at the time, Charles de Gaulle. Publishers weren’t interested – de Gaulle was still alive, so the ending was a foregone conclusion. Forsyth changed his tactics, and presented the manuscript to publishers with a cover note stating that the novel wasn’t about the success or failure of the mission, but rather in the details of the manhunt. London-based Hutchinson & Co. took a chance on publishing it; however, they only agreed to a relatively small initial printing of just 8,000 copies.

The Day of the Jackal was an instant sensation, earning international acclaim and being made into a movie in 1973. He’d write over 25 books, including The Odessa File and The Fourth Protocol, and sold 75 million books around the world.

His works required meticulous research – Jackal saw him visiting a professional forger to find out how to obtain a false British passport, and a gunsmith told him how to devise a rifle so slim it could be concealed in a crutch. He includes specific details about the particular functions of security officials and the paperwork needed to get through a police cordon. Writer Lee (“Jack Reacher”) Child said Forsyth changed the entire genre. “We all had to perform to that same level. There was a movement throughout thriller writing to concentrate on the detail, the research. An obvious example would be Tom Clancy. Could Tom Clancy have existed without Frederick Forsyth? Highly unlikely.”

Forsyth and Michael Caine, probably in 1984, talking about the movie version of The Fourth Protocol:

HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY (1670-2025)

That date is NOT a typo.

Chartered by King Charles II of England, the HBC began as a fur trading enterprise. Its royal charter granted it exclusive trading rights over the Hudson Bay watershed, which covers approximately 40 percent of present-day Canada. The company’s early trading posts, including York Factory, Fort Garry, and Fort Edmonton, were instrumental not only in commerce but in the westward expansion of European settlers.

As the fur trade declined in the 19th century, HBC transformed into a major landholder, selling large portions of its territory to the Canadian government in 1869. This transaction played a pivotal role in Canadian Confederation and western expansion. Over time, many of its trading posts evolved into general merchandise stores, setting the stage for its eventual transition into full-scale department store retailing.

By the 20th century, Hudson’s Bay had grown into Canada’s dominant department store operator, opening flagship stores across major cities. The chain became synonymous with Canadian family life, from back-to-school shopping and holiday gift-giving to bridal registries and household purchases. Its own private-label products, most notably the multistripe Hudson’s Bay point blanket, became recognized worldwide as Canadian icons.

But as the retail market began to change in the late 20th century, foreign investors started buying up shares in the company. Much of the rest was purchased by a private equity firm, which did to “HBC” what another private equity company did to Sears – sell off every profitable part, and leave the rest holding the debt.

The last few stores closed this summer; the company’s remaining assets are in limbo.

One of their iconic wool blankets, and a version of the company logo showing the same four stripes:

TOM LEHRER (1928-2025)

A story, from BlueSky:

I worked as a mathematician at the NSA during the second Obama administration and the first half of the first Trump administration. I had long enjoyed Tom Lehrer’s music, and I knew he had worked for the NSA during the Korean War era. The NSA’s research directorate has an electronic library, so I eventually figured, what the heck, let’s see if we can find anything he published internally! And I found a few articles I can’t comment on. But there was one unclassified article– “Gambler’s Ruin With Soft-Hearted Adversary”. The paper was co-written by Lehrer and R. E. Fagen, published in January, 1957.

The mathematical content is pretty interesting, but that’s not what stuck out to me when I read it. See, the paper cites FIVE sources throughout its body. But the bibliography lists SIX sources. What’s the leftover? …You can probably figure it out by looking at the bibliography.

See, entry 3 in the bibliography is “Analytic and Algebraic Topology of Locally Euclidean Metrizations of Infinitely Differentiable Riemannian Manifolds” by one N. Lobachevsky. And if you’ve ever heard Leher’s song “Lobachevsky“, you may have just finished that title with “Bozhe moi!”

Now, it’s important to note: this paper was published internally in 1957. Tom Lehrer had recorded and released “Songs by Tom Lehrer” in 1953, with “Lobachevsky” included. The song had already achieved some success….but nobody at the NSA noticed when he and Fagan dropped it in as a reference.

It struck me as a very Lehrer-ish sort of prank. It’s harmless, it’s light-hearted, and it thumbs its nose a bit at stuffy respectability through its unfailing pretense of seriousness.

How had other people reacted to the joke, I wondered?

So I sent an email to the NSA historians. And I asked them: hey, when was this first noticed, and how much of a gas did people think it was? Did he get in trouble for it? That sort of stuff.

The answer came back: “We’ve never heard of this before. It’s news to us.”

A few years later, I filed to have the paper declassified, and the NSA eventually agreed, and even put it up on their webpage:

Once that had happened, I wrote to Mr. Lehrer with a copy of the paper and a letter asking if he had ever gotten in trouble for it. He kindly wrote back, including a copy of the paper that had been published in Journal of SIAM in 1958, under a slightly different title. Nobody, he said, caught him.

An anecdote:

In 2013, Lehrer recalled the studio session for “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park”, which referred to the practice of controlling pigeons in Boston with strychnine-treated corn:

The copyist arrived at the last minute with the parts and passed them out to the band… And there was no title on it, and there was no lyrics. And so they ran through it, “What a pleasant little waltz”…. And the engineer said, “‘Poisoning Pigeons in the Park,’ take one,” and the piano player said, “What?” and literally fell off the stool.

He was appreciated by chemists, too…..

JACK MCAULIFFE (1945-2025)

While serving in the Navy, he found himself stationed in Scotland. In his free time, he motorcycled around the area, stopping at local pubs and breweries.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘Well, what in the world am I gonna do when I get back to the United States and they don’t have beer like this?’” he said in an oral history with Theresa McCulla, who chronicled the history of craft brewing as a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. He found an answer while reading The Big Book of Brewing by Dave Line, a British home-brew pioneer who inspired him to start making his own beers.

Settling in Northern California, he got two friends to help him scrounge, scavenge, and build his own equipment (commercially available gear was either for the hobbyist or large commercial brewers). The New Albion Brewing Company opened up in 1976, quickly gaining national media attention. Even with their small output, it was still too much for what was essentially a one-person operation. After failing to get backing to expand the brewery, McAuliffe closed its doors in 1982, and left the brewing business.

But not before Ken Grossman had paid two visits to see how things were being done. “After looking at Jack’s operation, we realized you can’t survive off a barrel and a half of beer” a day, Grossman said. “You can’t eat off that, let alone cover your costs.” When Grossman launched Sierra Nevada in 1980, its production capacity was seven times the size of New Albion’s.

As the microbrewery industry exploded, people would not forget who started it. In 2012, the Boston Beer Co. paid tribute to McAuliffe with the release of a New Albion pale ale. One of the company’s co-founders, Jim Koch, had acquired the rights to the New Albion name, and worked with McAuliffe to put out the beer using New Albion’s original recipe. He then donated the New Albion trademark, along with proceeds from the run — some $350,000, according to McCulla’s oral history — to McAuliffe, who used some of the money to build a small cabin in Arkansas.

McAuliffe gave the rights to New Albion’s name to his daughter, DeLuca, who was born out of a teenage relationship he had with one of his high school classmates, Linda Pellini. McAuliffe did not know he had a daughter until the two reconnected late in life. In 2013, she formed the Brewer’s Daughter to partner with third-party breweries to reproduce New Albion beers. A few years ago, DeLuca partnered with BrewDog, a brewery based in Scotland, to produce a limited run of New Albion pale ales at BrewDog’s outpost in Columbus, Ohio. The company had known about McAuliffe’s ties to Scotland, where his passion for beer took root.

“That,” DeLuca said, “was a full-circle moment.”

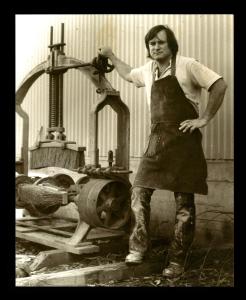

McAuliffe with his homemade barrel washer, circa 1979:

SHIGEO NAGASHIMA (1936-2025)

A native of Usui (now known as Sakura), Chiba Prefecture, Nagashima attended Rikkyo University and played for the school’s baseball team. Signed by the Yomiuri Giants after graduation, he would play third and bat right behind Sadaharu Oh. An instant star, he’d be named the Central League Rookie of the Year in 1958, when he led the league in home runs (29) and RBIs (92). He also hit .305 and stole 37 bases that year.

The next year, he’d hit one of the most important home runs in Japanese baseball history. On June 25, 1959, Emperor Hirohito and his wife, Empress Nagako, attended the game between the Yomiuri Giants and the Osaka (now Hanshin) Tigers at Korakuen Stadium in Tokyo. It was the first time a Japanese emperor had attended a pro game. With the score tied 4-4 in the bottom of the ninth inning, Nagashima stepped to the plate as the leadoff hitter. He crushed a high fastball from Tigers rookie Minoru Murayama over the left-field wall at 9:12 PM. It’s a moment etched in time in the national heartbeat of Japan. With the Emperor and Empress in attendance, professional baseball became respectable.

Nagashima was a five-time Central League MVP and received four Japan Series MVP accolades. He also won six CL batting titles and led the league in RBIs in five seasons. When he retired at age 38 in 1974, he had played in 2,186 regular-season games, smacking 444 home runs and recording 1,522 RBIs. He had a .305 career batting average and scored 1,270 runs.

The next year, he’d take over as the Giants’ manager, staying to 1980. “Mr. Pro Baseball” would take the helm again for 1993-2001, when he’d win two more Japan Series titles. The Giants would retire his number, and he was inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 1988.

That was not the end of honors. In 2013, he shared the spotlight with former Yomiuri and MLB slugger Hideki Matsui, when they were presented the People’s Honor Award by then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. He was also given the Order of Culture in 2021. No baseball player had previously won the prestigious award, which was established in 1937. And at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, Nagashima, Oh, and Matsui all helped carry the torch in the Opening Ceremonies.

And when his death was announced, newspapers published special “Extra” editions to be distributed on the streets…..

“I couldn’t match him at all in terms of presence, so I had to show it with my bat. I could only compete with him with my numbers. Shigeo Nagashima was the man inside the head of every pro baseball player.” – Sadaharu Oh

Japan Series managers Sadaharu Oh of the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks and Shigeo Nagashima of the Yomiuri Giants in October 2000:

MIKE RINDER (1955-2025):

Born in Adelaide, Australia, Rinder’s parents joined Scientology while he was a **09** and he grew up in the organization. At 18, he joined Scientology’s Sea Org, a senior level of staff within the organization. He continued his ascent in the organization and eventually became the executive director of the Office of Special Affairs, effectively becoming the chief media-facing representative of Scientology as well as, by his own admission, the chief practitioner of the PR dark arts, including smear and intimidation campaigns against journalists, ex-members and critics of Scientology. He worked there until his dismissal in 2005.

He broke with the organization in 2007, and soon found himself being targeted via the same OSA tactics he used. This turned him into an outspoken critic of the organization – and being as high up in it as he was, his words had a significant impact.

In 2013, he hooked up with actress (and former Scientologist) Leah Remini to produce a documentary series exposing the organizations methods. Running for 37 episodes on A&E, Scientology and the Aftermath won two Primetime Emmys, for outstanding informational series or special (2017) and outstanding hosted nonfiction series or special (2020), with Rinder receiving an Emmy for the latter win.

In the final post on his personal blog, Rinder wrote: “I have shuffled off this mortal coil in accordance with the immutable law that there are only two certainties in life: death and taxes…. My only real regret is not having achieved what I said I wanted to — ending the abuses of Scientology…. If you are in any way fighting to end those abuses, please keep the flag flying — never give up.”

Rinder and Remini (date unknown):

RONNIE RONDELL JR (1937-2025)

Ronald Reid Rondell was born into the movies. His father worked in Hollywood, and he accompanied his dad to movie sets — he liked to hang around the stunt performers — and got to be an extra in several “Ma and Pa Kettle” films.

While picking up a paycheck as an extra on a Western, he impressed actor Lennie Geer, who began schooling him in fights, falls and horseback riding. That led to him doubling for such actors as David Janssen on “Richard Diamond, Private Detective”, Robert Horton on “Wagon Train”, Doug McClure on “The Virginian” and Michael Cole on “Mod Squad”.

His later career spanned the ’80s and ’90s with credits in Blazing Saddles , Lethal Weapon, Thelma & Louise, Speed, The Crow, as well as coordinating stunts for Star Trek: First Contact, Batman & Robin, Sphere, and Deep Blue Sea.

In 2003, he even returned from retirement to stage a car-chase sequence in The Matrix Reloaded, working alongside his son, R.A. Rondell, the film’s stunt coordinator.

His work was celebrated with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Taurus World Stunt Awards in 2004 and induction into the Hollywood Stuntman’s Hall of Fame.

His most famous work was a still photo.

For the cover of the Pink Floyd album “Wish You Were Here”, art director Storm Thorgerson envisioned two businessmen shaking hands, one literally engulfed in flames, to evoke the metaphor of being “burned” by the deal. Photographer Aubrey “Po” Powell oversaw the shoot at Warner Bros. studios in Burbank, California. They had to shoot the scene fifteen times to get it to look right.

“You never told anyone you were hurt,” he said in Kevin Conley’s 2008 book, The Full Burn: On the Set, at the Bar, Behind the Wheel, and Over the Edge With Hollywood Stuntmen. “Because they always had another guy that could fit the clothes.”

BORIS CLAUDIO “LALO” SCHIFRIN (1932-2025)

Jazz composer whose movie scores include Cool Hand Luke, Dirty Harry, Rush Hour, and Bullitt.

When he was asked by the producer about his music for that scene in Bullitt, he said, “Silence is also music. The lack of music is going to make a great effect.”

And the work he’s best known for?

Morse Code for “M I” is dash dash; dot dot. Long, long, short, short….

(that’s him at the piano)

DOLORES “SISTER JEAN” SCHMIDT (1919-2025)

The oldest of three children, Dolores Bertha Schmidt was born in San Francisco on Aug. 21, 1919. Her father was a janitor and later a city administrator. She attended Catholic school. Her third-grade teacher, whom she adored, was a member of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. “Dear God,” she would pray at night, “help me understand what I should do, but please tell me that I should become a BVM sister.” In high school, she played on the girls’ basketball team.

In 1937, she joined the BVM, taking the name Sister Jean Dolores. She completed her bachelor’s degree in education in 1949. After teaching at elementary schools, Sister Jean received a master’s degree in education from Loyola University of Los Angeles (now Loyola Marymount) in 1961. That year, she joined the faculty at Mundelin College and then Loyola Chicago when Mundelin became affiliated with them in 1991.

Knowing of her basketball background, Loyola’s president asked her to work with Loyola’s athletes on improving their grades to help them remain eligible to play.

Athletes met with her weekly. She helped some write essays. She counseled others on time management. The meetings frequently drifted beyond academics. She prayed with athletes after family members died. She listened to them when their hearts were broken after relationships ended. Sister Jean was “the one person we knew we could always count on,” Derek Molis, one of the first players she worked with, told the New York Times in 2018.

In 1996, she was named the basketball team’s chaplain, where she added playing advice to her tutelage. “There’s been days throughout my last four years when I had a bad game, a down game,” Donte Ingram, a Loyola Chicago senior in 2018, told the Times. “We might have won. We might have lost. But at the end of the message, she always found a way to make me feel better.”

She was thrust into the national spotlight as the Ramblers staged an improbable run to the Final Four in 2018. After Loyola-Chicago’s buzzer-beating win over Miami in the first round, Sister Jean became an overnight celebrity — with photos and videos of her hugging players after the win going viral

Her bobblehead became the biggest seller in bobblehead history. Lego made a statue of her. “Sometimes I wonder, Why me?” she wrote in her autobiography. “Why did I become so famous? Why was I blessed with this kind of platform so that I could spread God’s grace and be an inspiration to others? I don’t know the answer.”

Finally, she concluded: “Our God is a God of surprises. Some are unpleasant, but many are wonderful. Things will happen in life that we could never anticipate. God likes to keep us on our toes. He has blessed me with an amazing life full of love and purpose. I can’t wait to see what He has in store for me next.”

BOBBY SHERMAN (1943-2025)

The son of a milkman, he showed a talent for music at an early age. He sang and learned to play a number of instruments, seeing performing as a way to overcome his shyness. Like a lot of people, he joined a band in high school and hoped to break in to the entertainment industry. Studying psychology at a community college, he got his break when a date invited him to a cast party for the soon-to-be released 1965 biblical epic The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Held at Sal Mineo’s house, the party had a lot of big Hollywood names in attendance – along with a band that included a couple of members of Sherman’s high school band. They needed a singer, and invited Sherman to join them on a couple of numbers. With his rendition of “What’d I Say” by Ray Charles, he caught the attention of movie stars Natalie Wood and Jane Fonda. Along with Mineo, they approached him at the end of the song. One of them said, “You’re very good. Who’s handling you?” Since he didn’t yet have a career, Sherman had no agent or manager or anyone “handling” him.

Shortly thereafter, Sherman received a phone call from an agent. He became a house singer on the variety show Shindig! and began making appearances on TV programs such as The Monkees. Stardom came when he landed a co-starring role on Here Come The Brides (a Western set in the logging boomtown of Seattle, where logging executives decide to recruit marriageable women to stave off loneliness among the lumberjacks) in 1968.

The next year he launched an even more successful singing career, with hits including “Easy Come, Easy Go” and “Julie, Do Ya Love Me”. For a while, the teen heartthrob was everywhere – posters, T-shirts, cereal boxes, lunch boxes…. After one performance, he had to sneak away in a hearse while fans mobbed a decoy limo…. Musical success eventually stopped, but he kept making TV appearances through the 1980s.

After his star faded, he chose an interesting second career. After taking a Red Cross class to learn how to care for his two sons if they were injured, he received his certification as an EMT. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department and instructed police academy trainees in first aid and CPR, becoming in the course of his work a sworn police officer and the department’s chief medical training officer. He also founded a volunteer EMT foundation, and, with his second wife, the Brigitte and Bobby Sherman Children’s Foundation, providing educational and nutritional services in Ghana.

Even in his new career, he still had his fans. One day, “we were working on a hemorrhaging woman who had passed out,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “Her husband kept staring at me. Finally he said, ‘Look, honey, it’s Bobby Sherman!’” The woman quickly came to and exclaimed, “Oh great, I must look a mess!” “I told her not to worry, she looked fine,” Mr. Sherman recounted. He then signed an autograph before the ambulance whisked her away.

A 1973 interview

CONRAD “GUS” SHINN (1922-2025)

Conrad Selwyn Shinn was born in Leaksville, North Carolina — a mill town that is now part of the city of Eden. As a boy, he idolized Charles Lindbergh and Wiley Post, pilot heroes of the golden age of aviation. His high school yearbook, which he edited, seemed almost prophetic in its title: The Pilot. He graduated at age 16, first in his class, and studied aeronautical engineering at North Carolina State College, now a university. He enrolled in a civilian pilot training program, left school to join the Navy in 1942 and received his commission the next year.

Shinn started out as a multiengine pilot in the South Pacific, transporting medical supplies and wounded men. He later flew military brass and other VIPs, ferrying flag officers, Cabinet secretaries and friends of President Harry S. Truman, before volunteering for Operation Highjump, a Navy program that brought him to Antarctica for the first time in 1947.

The Navy had been poking around in Antarctica for years, supporting scientific research and acquiring a foothold there in case it became strategically important. Shinn’s role in the operation was basically that of an aerial photographer; he spent a month at the Navy’s makeshift base on the Ross Ice Shelf.

Now at the rank of Lt. Commander, he returned to the Antarctic in as part of Operation Deep Freeze, a Navy mission that was launched in support of the International Geophysical Year, a collaborative effort promoting scientific research at the poles and elsewhere around the world.

One of his missions was to fly to the South Pole – to see if it was indeed possible to land and takeoff there. Piloting a propeller-driven R4D-5L named “Que Sera Sera”, he took seven passengers and crew. Upon landing (on October 31, 1956), after bouncing on the hard snow with skis affixed to its landing gear, the crew kept the engines running to prevent a freeze-up, Rear Adm. George J. Dufek stepped outside into the 60 below environment and planted an American flag into the ice. (Technically, they had landed about four miles from the geographical South Pole. Observers deemed it close enough.) The group set up a metal radar reflector, intended to help future pilots make their way to the site, and spent about 45 minutes outside before readying for takeoff.

This was the third time people had reached the South Pole…..

Unfortunately, because they’d left the plane’s engines running to prevent freezing, the snow under its skis had melted and refrozen. They were stuck. “We just sat on the ice like an old mud hen,” he told the Associated Press in 1999. Fortunately, the plane was equipped with a “JATO” system: rockets that would assist in difficult takeoffs. Shinn managed to free the plane and just barely take off. The next month, the Navy began building a permanent base at the South Pole.

As a result of the mission, Cmdr. Shinn was awarded the Legion of Merit. Antarctica’s third-highest peak, Mount Shinn, was named in his honor.

“I had been lucky,” he said in the oral history, looking back on his flying days in the Antarctic. “Lucky — that’s what I would call it.”

Cmdr. Shinn retired from the Navy in 1963 and settled in Pensacola, where he had been stationed. For years, he made regular visits to the National Naval Aviation Museum, where he was able to visit his restored former plane, the Que Sera Sera, and tell visitors about his flying days.

Shinn and the Que Sera Sera in 2016:

SKYPE (2003-2025)

Founded in Tallinn, Estonia, in 2003, by Niklas Zennström and Janus Friis, the service’s VoIP technology allowed free calls between its users, bypassing traditional phone companies and their expensive call rates. It was bought by eBay in 2005 for $2.6 billion, who added video calls. At its peak, it had some 300 million users.

“Skype was a broadening of horizons in my mind,” technology journalist and broadcaster Will Guyatt said in a phone interview Monday, recalling how he became a user when it first launched. At the time, he said, it was a novel way to keep in touch with friends who had moved abroad or were traveling. “It was quite eye-opening — the fact that you could make decent calls to people on computers and then pretty soon after that solid video calls,” he recalled. “It made it simple and easy to do.”

Microsoft purchased the service in 2011 for $8.5 billion – its largest acquisition to that time.

Usership declined as competitors like Zoom and WhatsApp provided better quality with an easier interface and better reliability.

The service is being folded into Microsoft’s own “Teams” service / app.

The news of Skype’s closure prompted a flood of nostalgia from other users online. For some millennials, Skype’s heyday coincided with coming-of-age moments, and its familiar bubbly ringtone conjured up core memories:

“Many memories were shared through late-night calls and laughter. You connected us across miles and time zones. Goodbye, old friend.”

“Goodbye, Skype… You stuttered, you froze, and you disconnected… But, you served us well in times of need.”

BORIS SPASSKY (1937-2024)

Born in Leningrad, he and his brother were evacuated from the city when it was under siege by the Germans in The Great Patriotic War. His parents would barely survive the siege. After their return to Leningrad, when he was nine years old, his brother took him to Krestovsky Island, and there he saw a chess pavilion. It was there where he fell in love with the game. “Looking back, I had a sort of predestination in my life. I understood that through chess I could express myself, and chess became my natural language.”

Spassky always said that he “became a professional at 10” when he started working with his first coach, Vladimir Grigorievich Zak, at the Leningrad Palace of Pioneers in 1947. Zak trained him but also fed him in times of severe poverty, and helped him to get a stipend, enough to support his whole family. He rose through the ranks, becoming World Junior Champion in 1956. He attended Leningrad University, majoring in journalism largely because the head of that department allowed him to take time off to attend chess training camps and tournaments. It didn’t matter anyway; chess would become his career.

He had second thoughts after a disastrous loss to future World Champion Mikhail Tal in 1958. “After my loss to Tal, I went out into the street. I was absolutely depressed, tears were running down my cheeks… Suddenly, while walking I met David Ginsburg, the journalist who had worked in the chess newspaper 64 before the war and was later sent to the Gulag. ‘Is it worth being so upset?’ he asked me. ‘Well, Tal will play his match with Botvinnik, and he will win the title. But later he will lose the return match to Botvinnik. Some time later Petrosian will become world champion, and then your turn will come…’”

His turn came in 1969, when he defeated Tigran Petrosian to become the 10th World Champion of chess.

Three years later, he would defend his title against Bobby Fischer. According to the rules of the competition, Spassky could have claimed victory after Fischer forfeited the second game:

Some days before the start of the third game I spoke for half an hour on the telephone with Pavlov, the president of the Soviet Sports Committee. He demanded that I should declare an ultimatum which, I was sure, Fischer, [FIDE president Max] Euwe and the organizers would have never accepted; so, the match would be broken off. The whole telephone conversation was just a never-ending exchange of two phrases: ‘Boris Vasilievich, you must declare an ultimatum!’; to which I responded, ‘Sergei Pavlovich, I shall play the match!’

“After Reykjavik, the Sports Committee couldn’t forgive me for declining the chance to retain the world championship title. I could easily have done that simply by leaving the match. I had every justification, with FIDE President Max Euwe even telling me: ‘Dear Boris, you can quit the match at any moment. Take as much time as you need, go to Moscow or wherever else, but recover and think things over.’ I replied: ‘Thanks for the good advice, Max, but I’ll do things my way.’”

Spassky would continue to compete – and win – but wouldn’t regain the World Championship.

In 1976, the Soviet Union allowed him to move to Paris, which allowed him to choose for himself which tournaments to play. He became a French citizen in 1978 but kept playing under the Soviet flag until 1984.

He’d meet Fischer for a rematch in 1992, with a similar result (Fischer won). The pair actually became friends, and would call and chat about chess until Fischer’s death in 2008. That was the last major match he’d compete in, though he’d appear in the occasional tournament until 2009. “I felt that I had no more energy to play, that I had lost any desire to win.”

His health declined, and he moved back to Moscow in 2012. In February 2018 he was elected honorary president of the Russian Chess Federation.

“[His play] does not lend itself to a distinct division into any clearly expressed components, making it unique and unrepeatable. With Spassky everything is somehow diffuse and misty—and this, evidently, confirms his image of a universal chess player. It is generally considered that the universal chess style, involving an ability to play the most varied type of positions, stems from Spassky.” – Garry Kasparov

“Spassky sits at the board with the same dead expression whether he’s mating or being mated. He can blunder away a piece, and you are never sure whether it’s a blunder or a fantastically deep sacrifice.” – Bobby Fischer

“He was not only a wonderful champion, but also a fascinating personality. Anyone who met him will surely remember him – forever. His character came through in every possible way, especially with his sense of humour, his brilliant mind, his facial expressions. He turned to chess and life with GREAT curiosity.” – Judit Polgar

“In general, what a chess player needs has always been the same, with a love of chess the main requirement. Moreover, it has to be loved naturally, with passion, the way people love art, drawing, and music. That passion possesses you and seeps into you. I still look at chess with the eyes of a child.” – Boris Spassky

DREW STRUZAN (1947-2025)

Born in Oregon City OR, he loved drawing, using whatever materials he could get. He went to the ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles to further his career. He worked his way through that school selling his artwork and accepting small commissions.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree, he landed a job as a staff artist for Pacific Eye & Ear, a design studio. After designing album covers for acts including The Beach Boys, the Bee Gees and Earth, Wind & Fire — for just $150 to $250 a piece — he moved into movie posters in 1975.

His big break came in 1978 when he was hired to help create the poster for the re-release of Star Wars, painting the human characters in oil while fellow artist Charles White III handled the mechanical details. His “circus poster,” designed to evoke turn-of-the-century carnival art, became an instant classic. It was reportedly George Lucas’ favorite of the many Star Wars posters, and Lucasfilm hired him on for several projects.

From there, Struzan became Hollywood’s go-to “one-sheet wonder,” creating unforgettable posters for Blade Runner, The Goonies, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, The Thing, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and many more.

“His posters made many of our movies into destinations … and the memory of those movies and the age we were when we saw them always comes flashing back just by glancing at his iconic photorealistic imagery.” – Stephen Spielberg

Struzan himself once explained his philosophy: “I felt that art was more than just telling the story.… I asked the directors what they’re doing and why they were doing it. I try to find the best in what they are doing, then I paint that way.”

Drew (l) receiving a tribute poster from fellow poster artist Kyle Lambert:

BOB UECKER (1934-2025)

He joined the Army after high school, playing baseball on bases in Missouri and Virginia. He got good enough to attract some notice from the Milwaukee Braves, who would eventually sign him for a $3,000 bonus.

“It was a lot of money, but my father eventually scraped it together….”

After six years in the minors, he was finally called up to the majors where he became the Braves’ backup catcher. He was traded to the Cardinals at the start of the 1964 season, and helped them win the World Series, where he did not appear.

“I came down with hepatitis. The trainer injected me with it.”

He was traded to the Phillies after the next season, and back to the Braves (now in Atlanta) in the middle of 1967 when the team needed a catcher who could work with Phil Niekro on the latter’s knuckleball. In fact, Niekro credited his Hall of Fame success to his catcher, writing in his autobiography that Uecker “ingrained in my mind that I shouldn’t be afraid to throw the knuckler. What happened to it after it left my hand was not my responsibility, but instead his.”

“I led the league in passed balls that year, and I didn’t even play every game…. I met so many wonderful people that year. They all sat right behind home plate.”

He retired after that year, and dabbled a bit in broadcasting and stand-up comedy. After seeing him open for Don Rickles, Al Hirt recommended Uecker to his agent, who got him a spot on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson. That led to over 100 appearances on that show for “Mr. Baseball” After the first couple of times, Ueck was never asked to do a pre-show interview. Carson didn’t want to know what he was going to say. He just knew it would be gold.

When the Brewers began in Milwaukee 1970, owner Bud Selig hired him to be a scout. That didn’t work out, but the next year he landed in the team’s radio booth – where he would stay as the voice of the team for over 50 years.

“To be able to do a game each and every day throughout the summer and talk to people every day at 6:30 for a night game, you become part of people’s families,” Uecker once said. “I know that because I get mail from people that tell me that. That’s part of the reward for being here, just to be recognized by the way you talk, the way you describe a game, whatever.”

That success got him spots in TV commercials, and soon a real TV acting career. From 1985 to 1990, he starred in the ABC sitcom “Mr. Belvedere” as a sportswriter who hires a prissy English butler to manage his household. He’s better known for playing the broadcaster Harry Doyle in 1989’s comedy, Major Leauge, where he drew on his experience to ad-lib almost all his lines.

He’d often joke about being overlooked by baseball’s Hall of Fame….

“It finally got to the point,” he told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “where I had to say, ‘Hey, I don’t need it.’ I can bronze my own glove and hang it on a nail in my garage.”

…but im 2003, he was made a Hall of Famer by being honored with the Ford C. Frick Award for excellence in broadcasting. His acceptance speech was a distillation of his comedy routines over the years.

“I had a great shoe contract and glove contract with a company who paid me a lot of money never to be seen using their stuff.”

Time took its toll, and he had to cut back on his work in the booth. But he was never far from the Brewers. He really did have a good throwing arm, and would often pitch batting practice for the team well into his 70s. In 2018, when the Brewers made the run all the way to the National League Championship Series, they voted him a full share (which he donated to charity).

After the Brewers were eliminated from the playoffs in 2024, Uecker’s last season, he made sure to visit the locker room and offer support to players in a way only he could. Brewers outfielder Christian Yelich said afterward the toughest part of the night was talking to Uecker because the Brewers knew how badly the longtime broadcaster wanted to see Milwaukee win a World Series, and this was almost certainly going to be his last chance. “I remember you saying that no matter how much time you have, it still never feels like enough, and that seems pretty true today,” Yelich said in an Instagram post. “You’d always thank me for my friendship, but the truth of it is the pleasure was all mine. I’ll miss you, my friend.”

Uecker goofing off before a 1964 World Series game: